| Line 840: | Line 840: | ||

On Tuesday, 31 March 2020, all 3 plaintiffs announced that they would be appealing the [[High Court]]'s ruling[https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/all-three-men-to-appeal-dismissal-of-their-challenges-against-12592934]. |

On Tuesday, 31 March 2020, all 3 plaintiffs announced that they would be appealing the [[High Court]]'s ruling[https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/all-three-men-to-appeal-dismissal-of-their-challenges-against-12592934]. |

||

| − | =Roy Tan files |

+ | =Roy Tan files High Court application for mandatory order compelling Cabinet to move Bill in Parliament to repeal 377A= |

: ''See also: [[Remedies in Singapore administrative law]]'' |

: ''See also: [[Remedies in Singapore administrative law]]'' |

||

On 1 December 2020, [[Roy Tan]], filed an application in the [[High Court]] seeking a [[declaration]] that Section 377A of the Penal Code was incongruent and inconsistent with [[Section 119 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|Sections 119]] and [[Section 176 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|176]] of the [[Penal Code]], [[Section 17 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|Sections 17]] and [[Section 424 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|424]] of the [[Criminal Procedure Code]], [[Section 9A (1) of the Interpretation Act]] and [[Article 9 of the Constitution of Singapore|Articles 9(1)]] and [[Article 12 of the Constitution of Singapore|12(1)]] of the [[https://the-singapore-lgbt-encyclopaedia.wikia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Singapore|Constitution of the Republic of Singapore]]. He also argued that the [[Attorney-General]]’s position - that it would naturally follow that any prosecution under other provisions which would contradict the non-prosecution stance for male [[homosexual]] adults indulging in [[consensual]] sex in private would likewise not be in the public interest - rendered Section 377A [[otiose]] [[a fortiori]]. |

On 1 December 2020, [[Roy Tan]], filed an application in the [[High Court]] seeking a [[declaration]] that Section 377A of the Penal Code was incongruent and inconsistent with [[Section 119 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|Sections 119]] and [[Section 176 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|176]] of the [[Penal Code]], [[Section 17 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|Sections 17]] and [[Section 424 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|424]] of the [[Criminal Procedure Code]], [[Section 9A (1) of the Interpretation Act]] and [[Article 9 of the Constitution of Singapore|Articles 9(1)]] and [[Article 12 of the Constitution of Singapore|12(1)]] of the [[https://the-singapore-lgbt-encyclopaedia.wikia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Singapore|Constitution of the Republic of Singapore]]. He also argued that the [[Attorney-General]]’s position - that it would naturally follow that any prosecution under other provisions which would contradict the non-prosecution stance for male [[homosexual]] adults indulging in [[consensual]] sex in private would likewise not be in the public interest - rendered Section 377A [[otiose]] [[a fortiori]]. |

||

| − | Tan, represented by lawyer [[M Ravi]], furthermore sought a [[ |

+ | Tan, represented by lawyer [[M Ravi]], furthermore sought a [[mandatory order]] compelling the members of the [[Cabinet]] to move a [[Bill]] in [[Parliament]] to repeal Section 377A because the latter has become [[dead letter]] and its retention in the face of [[Section 17 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|Sections 17]] and [[Section 424 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Singapore)|424]] of the [[Criminal Procedure Code]], [[Section 119 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|Sections 119]] and [[Section 176 of the Penal Code (Singapore)|176]] of the [[Penal Code]] and [[Section 9A of the Interpretation Act]] was unlawful due to the [[Executive]]’s decision not the enforce Section 377A. Under [[Section 9A (1) of the Interpretation Act]], the courts were required to interpret a written law in a way that promoted the purpose or object underlying that law. [[Parliament]]'s undertaking not to proactively enforce Section 377A rendered the courts unable to perform their legal obligation. |

=See also= |

=See also= |

||

Revision as of 03:12, 3 December 2020

Section 377A of the Penal Code of Singapore is the main persisting piece of legislation which criminalises sex between mutually consenting males who are not below the legal age of consent (16 years in Singapore), even when it is done in private. In lay terms, it is known as the "gross indecency" law. This is the phrase commonly used by the press when routinely reporting on criminal cases charged under the statute.

- Consensual sex between males where one party is underaged is charged under commercial sex with a minor below 18, sex with a minor below 16 or statutory rape.)

- Non-consensual sex between males is charged under "assault or use of criminal force to a person with intent to outrage modesty" (Section 354 of the Penal Code[2]). Male on male rape is charged under Section 375 (1A) of the Penal Code[3]. Sexual assault involving penetration (eg. performing oral sex on another non-consenting male) is charged under Section 376 of the Penal Code. Victims are not charged. (See main article: Rape of males in Singapore).

"Gross indecency" is usually taken to mean all forms of non-penetrative sex (eg. mutual masturbation) between two males regardless of age. This stands in contrast with the former Section 377, known as the "unnatural sex law", which included only penetrative sex (mainly oral and anal) between two persons of any gender, meaning it did not discriminate between heterosexual and homosexual sex. After the repeal of the erstwhile Section 377 in 2007, a legal anomaly arose whereby non-penetrative sex between men was criminalised while more serious penetrative sex was not.

The Penal Code (Chapter 224): Chapter XVI: Offences affecting the human body: Sexual offences: Section 377A (Outrages on decency)[4] states:

"Any male person who, in public or private, commits, or abets the commission of, or procures or attempts to procure the commission by any male person of, any act of gross indecency with another male person, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 2 years."

Origin

To understand the background of Section 377A, the enactment of its mother statute, the original Section 377 which criminalised sex "against the order of nature" and was popularly known as the "unnatural sex" law, must first be explained. It banned penetrative sex (oral and anal) between two people regardless of gender if the act did not immediately lead to penile-vaginal intercourse which was considered the only form of "natural" sex as it had the potential of procreation.

The former Penal Code (Chapter 224): Chapter XVI: Offences affecting the human body: Sexual offence: Section 377 (repealed in 2007) stated:

"Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animals, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine.

Explanation. Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this Section."

Ecclesiastical roots in Britain under Henry VIII

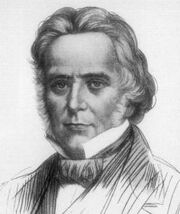

Henry VIII, the monarch who enacted Britain's anti-sodomy laws.

An exhaustive analysis of the origin of British laws which sought to prohibit buggery and their evolution into Section 377 is found in a seminal academic paper by Prof. Douglas Sanders (see archive of the paper: 377 and the unnatural afterlife of British colonialism).

Prosecution by the Catholic Church

Prior to the enactment of the first civil anti-buggery law in Britain in 1533, the offences of buggery or sodomy had been dealt with by the Catholic Church. In the Church's early medieval years, these acts were given no particular penance. They were viewed like all the other sins[5]. Despite the extreme gravity with which the Church viewed "unnatural" vice, remarkably little conciliar legislation up to the 12th century was devoted to homosexuality. Considerably more was said about adultery, incest and concubinage. The penalty for sodomy, in pre-12th century and later legislation, was largely penitential and not judicial. One can only speculate whether this meant that the accused had to recite fifty Hail Marys upon conviction with sodomy rather than being imprisoned or physically castigated. In any case, it was extremely rare that men were brought up to the ecclesiastical courts for homosexual behavior alone. From 1470 to 1516, only 1 out of 21,000 church trials was for sodomy, and the accused was simply excommunicated when he failed to appear. In medieval Church law, individuals were more commonly charged for publicly standing up against the Church for its norms which looked down upon homosexuality. If they refused to back down from their "heresy", they were severely punished. The usual punishment for convicted heretics was death by burning at the stake.

The Buggery Act

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punysshement of the vice of Buggerie, was an Act of the Parliament of England piloted by Henry VIII's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell.

The Act prescribed death as the punishment for buggery with man or beast. Some have suggested that bestiality was specifically included because of the fear of hybrid births!

The phrasing used in the Buggery Act, which included the word "abominable" (taken from the Book of Leviticus in the Bible), in addition to "buggery" (which, by the 13th century, had become associated with sodomy and was later defined by the courts to include only anal penetration and bestiality) and "vice", confirms its religious character.

The Buggery Act 1533 stated:

"Forasmuch as there is not yet sufficient and condign punishment appointed and limited by the due course of the Laws of this Realm for the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with mankind of beast: It may therefore please the King's Highness with the assent of the Lords Spiritual and the Commons of this present parliament assembled, that it may be enacted by the authority of the same, that the same offence be from henceforth ajudged Felony and that such an order and form of process therein to be used against the offenders as in cases of felony at the Common law. And that the offenders being herof convict by verdict confession or outlawry shall suffer such pains of death and losses and penalties of their good chattels debts lands tenements and hereditaments as felons do according to the Common Laws of this Realme. And that no person offending in any such offence shall be admitted to his Clergy, And that Justices of the Peace shall have power and authority within the limits of their commissions and Jurisdictions to hear and determine the said offence, as they do in the cases of other felonies. This Act to endure till the last day of the next Parliament."

Walter Hungerford was the first man to be executed under the Buggery Act.

This meant that a convicted sodomite’s possessions could be confiscated by the government, rather than going to their next of kin, and that even priests and monks could be executed for the offence since it was a law enacted "without benefit of clergy". This was ironic, in view of the fact that priests and monks could not be executed even for murder. Henry VIII later used the law to exterminate monks and nuns (thanks to information his spies had gathered) and appropriate their monastery lands. The same tactics had been used 200 years before by Philip IV of France against the Knights Templar.

The Buggery Act was formulated in the context of Henry VIII's engineered break from papal authority to establish the Anglican church via the English Reformation. It bolstered Henry's position against the Catholic Church's courts. More practically, it aimed to justify the seizure of the Catholic monasteries and the confiscation of their other rich properties. The pretext was the alleged sexual immorality of those in the religious vocation. Without this anti-Catholic agenda, it seems unlikely that the Act would have been enacted. The use of the sodomy law, more than just going after people who engaged in homosexual intercourse, was thus also part of religious persecution.

In July 1540, contravention of the Act, along with treason, resulted in the first conviction. Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford of Heytesbury, became the first person executed under the statute, although it was probably the treason that cost him his life. Being a nobleman, he was beheaded at Tower Hill, an elevated spot northwest of the Tower of London (commoners were hung at another public execution site, Tyburn). Ironically, Thomas Cromwell, the man who introduced the Buggery Act to parliament, was also beheaded there the very same day, on 28 July 1540, after he fell out of favour with Henry VIII. Nicholas Udall, a cleric, playwright and headmaster of Eton College, was the first to be charged for violation of the Act alone in 1541. In his case the sentence was commuted to imprisonment, and he was released in less than a year.

When the staunchly Catholic Mary I of England, Henry VIII's elder daughter, ascended the throne in 1553 and aggressively returned England to Catholicism, in spite of all the executions she ordered which earned her the nickname of Bloody Mary, she surprisingly struck down her father's sodomy law. Evidently, she did not do this because of prevailing Catholic policy during the time since other Catholic states still criminalised sodomy but she preferred such legal matters to be adjudicated in ecclesiastical courts. After Mary's death in 1558 during an influenza epidemic, her half-sister Queen Elizabeth I reinstated Henry VIII's Buggery Act in 1563.

Offences against the Person Act & Criminal Law (India) Act

The Buggery Act remained in force until its repeal in 1828. It was replaced by Section 15 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828, and Section 63 of the Criminal Law (India) Act 1828, which provided that buggery would continue to be a capital offence.

Buggery remained a capital offence in England and Wales until the enactment of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. The last execution for the crime took place in 1836.

Codification of law, particularly criminal law, became a major reform project in Britain in the 19th century, pushed by Jeremy Bentham and the utilitarians. Codes were well suited to British colonialism, providing a single, orderly written version of areas of law. This made them easy to enact in a colony.

Indian Penal Code

Lord Thomas Macaulay.

In the early years of British colonialism in the East, the British government enacted several Indian Charter Acts which gave the East India Company exclusive rights of trade and commerce in India and subsequently, also the right to rule its largest colony. Amongst these was the Charter Act of 1833 which introduced legislative centralisation in India and extended the tenure of the commercial grant of the company for another 20 years. The Charter Act of 1833 required the appointment of a Law Commission to consolidate, codify and improve the “splintered (legal) systems prevailing in the Indian Subcontinent”. Lord Thomas Macaulay was appointed president of that commission in 1835. He drafted the Indian Penal Code with the help of many experienced lawyers to replace Hindu criminal law. The latter was based on the Manusmriti, generally known in English as the Laws of Manu or "Dharmic discourse to Vedic rishis" on the "way of living" for various classes of society, and which had hitherto held sway in the greater part of India.

Macaulay’s first draft of the Penal Code contained a Clause 361, which prescribed a severe punishment for touching another with the purpose of satisfying unnatural lust. Macaulay abhorred the idea of any discussion or debate on this "heinous crime" and in the Introductory Report to the proposed draft Bill dated 1837 stated:

"Clause 361 and 362 relate to an odious class of offences respecting which it is desirable that as little as possible should be said...[we] are unwilling to insert, either in the text or in the notes, anything which could give rise to public discussion on this revolting subject; as we are decidedly of opinion that the injury which would be done to the morals of the community by such discussion would far more than compensate for any benefits which might be derived from legislative measures framed with the greatest precision."

The lack of any debate, suggesting the creation of this definition purely at the discretion of Macaulay, also explains the sheer vagueness and ineffectiveness of the language of the proposed anti-sodomy section. The concept of an "unnatural touch" was too woolly to be an efficacious penal statute, and the final version proved to be a substantial improvement on the initial draft. Macaulay's final copy included a Section 377, a statute based on English criminal law which sought to prohibit "buggery" or sodomy, largely taken to mean anal sex between men. The Indian Penal Code was finally incorporated by the British colonial administration in the late 1850s.

Hindu temple sculptures in Khajuraho depicting homosexual sex. (See also Hinduism and LGBT topics)

Under Hindu law, consensual sex between adult males was never an offence. The classic Indian text, Kama Sutra, dealt without ambiguity or hypocrisy with all aspects of sexual life including marriage, adultery, prostitution, group sex, sadomasochism, male and female homosexuality, and transvestism. In the new Indian Penal Code, however, Section 377 criminalised "carnal intercourse against the order of nature". The latter phrase was a new legal concoction, not previously found in British law. It was derived from words attributed to, amongst others, Thomas Aquinas and Sir William Blackstone. A fine and/or up to 10 years' imprisonment were specified for these activities. It is ironic that Lord Macaulay never lived to see his infamous unnatural sex law, which was to wreak so much misery on the lives of homosexual men throughout Britain's colonies for well over a century, come into force in India. Also, despite his apparent revulsion for homosexuality, Macaulay himself never married and his closest companion was his sister Hannah.[6] (For a detailed history of Macaulay's enactment of India's Section 377, see archive of the academic paper, "Section 377 and the dignity of Indian homosexuals" by Alok Gupta).

Colonial diffusion

Section 377 became effective as part of the British-imposed Indian Penal Code from 1 January 1862, and was adopted by the colonial masters, also as "Section 377" into the Straits Settlements Penal Code in 1871. The cloned and transplanted law came into operation in the Straits Settlements of Singapore, Penang and Malacca on 16 September 1872.

Similarly worded legislation, also under the same numbered section of each country's penal code, that is, "377", as if it were a trademark, was introduced by the British into their other Asian colonies such as India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Malaya (now Malaysia), Brunei and Burma (now Myanmar) in the late 19th century.

Sri Lanka, the Seychelles and Papua New Guinea have the key wording from India's Section 377, but different article numbers. Parallel wording appears in the criminal laws of many former British colonies in Africa.[7]

Section 377A (Outrages on decency) was added to the sub-title "Unnatural offences" in the Straits Settlements Penal Code in 1938. Both Sections were absorbed unchanged into the Singapore Penal Code when the latter was passed by Singapore's Legislative Council on 28 January 1955.

Scope

The original Section 377 (repealed in October 2007)

Unnatural sex or sodomy was not defined in the Indian Penal Code drafted by the British. Legal records show that Indian legislators in the 19th and early 20th centuries interpreted "carnal intercourse against the order of nature" between individuals (of all sexes - the law being non-gender specific with its use of the word "whoever") to include anal sex, bestiality and, often after much courtroom deliberation, oral sex as well; namely, any form of sexual intercourse which did not have the potential for procreation.

Therefore, both heterosexual and homosexual oral and anal sex were criminal offences under the same law. In this respect, Section 377 did not discriminate against homosexuals. The latest eminent example of this was demonstrated on Tuesday, 27 August 2019 when an ex-primary school vice-principal was charged and found guilty under the former Section 377 because the offences were committed before the statute was repealed in 2007. The vice-principal had sexually groomed a student for years from when he was 14, eventually taking him into his own home, and performing occasional oral sex on him[8].

However, early cases tried under Section 377 in India mainly involved forced fellatio with unwilling male children, and one unusual case in 1934, Khandu vs. Emperor, of sexual intercourse with the nostril of a water buffalo (see Khandu vs Emperor, AIR, Lahore, 1934,[9],[10]).

Theoretically, even lesbian sex which involved penetration, eg. of a finger, tongue or sex toy into the vagina or anus, would be covered under the law, although there are no records of any judge in India or Britain's numerous other colonies interpreting the law to include sex between women.

In the Singaporean context, recent cases had established that heterosexual fellatio was exempted if indulged in as foreplay which eventually led to coitus. The Singaporean margin note of the original Section 377 further explained that mere penetration of the penis into the anus or mouth even without orgasm would constitute the offence. The law applied regardless of the act being consensual between both parties and done in private.

Owing to overwhelming public support after the 2003 Annis Abdullah case in which a policeman was convicted under Section 377 and sentenced to 2 years' jail for having consensual oral sex with a 16-year-old girl, and the realisation by the politico-legal system that the statute was no longer relevant to contemporary society, Section 377 was repealed in October 2007 during the extensive review of the Singapore Penal Code. A new Section 377, which criminalised sex with dead bodies ("Sexual penetration of a corpse")[11], was substituted in its place.

Enactment of Section 377A

Inspector-General René Onraet reported in 1937 that "male prostitution" was widespread in Singapore.

In 1937, René Onraet, the then Inspector-General of the Straits Settlements Police Force, submitted his annual report to Singapore's colonial government on the state of crime on the island, noting that with regard to vice, "male prostitution" was widespread. Historical correspondence provides evidence that the document caused the government to institute "a policy…to stamp out this evil" and was a prelude to making such acts between men a criminal offence so that male prostitution could be policed[12],[13]. However, it must be stressed that "male prostitution" was not solely targeted but all forms of sex work and pimping which the authorities regarded as "social evils".

One year after Inspector-General Onraet's report, Section 377A was introduced in 1938 by the Legislative Council into the Straits Settlements Penal Code to criminalise all non-penetrative sexual acts between men, eg. mutual masturbation and frottage. Onraet's follow-up progress dossier entitled, "Annual report on the organisation and administration of the Straits Settlements police and on the state of crime for the year 1938" (page 414, paragraph 48), published in 1939, announced that "male prostitution and other forms of beastliness were stamped out as and when opportunity occurred." The news was also carried in a Straits Times article dated 21 July 1939, on page 14[14]. Examining historical correspondence of the colonial government, it is apparent that 377A was enacted to enable male prostitution to be surveilled and also perhaps to protect European expatriates and visitors from the vice. It was not meant to prosecute adult males who indulged in consensual sex in private. This inference is in line with the fact that one of the first reported offences under Section 377A involved a British captain, Douglas Marr, who was charged for but acquitted of illegal homosexual acts with a Singaporean Malay male youth, Sudin bin Daud, at the captain's home in 1941[15],[16],[17] (also see below).

Between 2014 and 2016, further relevant documents from the United Kingdom’s National Archives were declassified which provided additional evidence that Section 377A was meant to target commercial sex rather than to criminalise consensual gay sex between men. A 1940 report which was declassified in 2016 showed that the enactment of Section 377A was in response to an “outbreak” of male prostitution in Malaya at the beginning of 1938. The report was addressed to George Gater, who held the title of Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies and made it apparent that there was a relationship between the two events. The report detailed two cases in 1938, the year the law was enacted. The first, which took place three months before Section 377A came into effect, involved a colonial official named Reeves who was suspected of having relations with male prostitutes but was not charged initially as there was no proof. The second case involved another official, Rivaz, who was sacked as the charges, similar to those made against Reeves, were justified following the enactment of Section 377A. Another incident, described in a document dated 24 March 1938 which was declassified in 2014, was one in which a European warder of the Straits Settlements Prisons, Moses, resigned after being caught in January 1938 attempting to sodomise two male prostitutes. This document was a communication from Sir Thomas Shenton, governor and high commissioner of the Straits Settlements, to the secretary of state for the colonies. There was evidently a problem within the civil service of civil servants patronising male prostitutes and it was this that gave rise to the law.

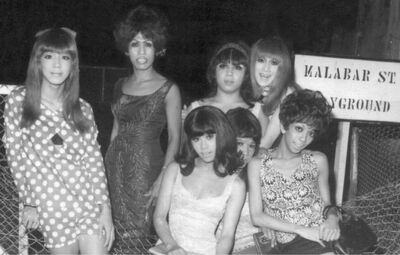

Transwoman sex workers, often mistakenly referred to as "male prostitutes", or even as "catamites" by the authorities, posing near the Bugis Street area in the 1960s.

"Male prostitution" during that era most likely referred to sex work by male-to-female cross-dressers or transvestites, a phenomenon which was rampant. Prostitution by non cross-dressing, outwardly male sex workers, known contemporarily as "rent boys" and, more recently, as "money boys" after the recent mainland Chinese influx, was almost unheard of then.

One possible reason why the British sought to enact Section 377A, even though they already had and could use the non-gender specific Section 377 to charge transwoman prostitutes and their clients was that the police must have found it difficult to use Section 377 to prosecute cross-dressers, who were legally men, for having sex with their male clients if prima facie evidence of anal or oral sex could not be produced. In these cases, a new law such as Section 377A which was vague enough to convict any form of non-penetrative sexual activity between men, or more accurately, a cross-dressing man and his outwardly male partner, could be used as a backup. The fact that two "men" were seen fondling each other or perhaps merely found naked together in a brothel room would be sufficient for a charge to be made against them. This was exactly how the Labouchere Amendment from which Section 377A is derived (see below) was used in the UK from the late 19th century onwards.

It is highly unlikely that in the 1930s, Section 377A was introduced to curb consensual sex in private between men who were both outwardly male in appearance as these activities had a much lower profile, were largely invisible to the public eye and were non-commercial in nature. However, in future decades, especially beginning in the latter half of the 1980s after the arrival of HIV/AIDS in Singapore, the existence of the law enabled the police to harass homosexuals who cruised in public places and to charge them if they had sex. The law has since been used mainly for this purpose, even though it was not the initial intention of the British colonial legislators.

Early prosecutions

Between 1938 and 1941, seven high-profile cases of prosecution under or related to Section 377A happened. Although four cases involved Europeans, only one was convicted.

In September 1938, Lim Eng Kooi and Lim Eng Kok became the first to receive punishment in the Straits Settlements. The two "well-known" Penang Chinese were sentenced to seven months imprisonment each under Section 377A[18].

In March 1941, a Tan Ah Yiow was sentenced to nine months imprisonment after he was found with a "European client" in a "low down quarter", where he was discovered by F. J. C. Wilson, head of the local Anti-Vice Branch, following a tip. Wilson added that in court that a "disgusting and revolting practice had been performed", with medical evidence forthcoming[19].

In April 1941, Lee Hock Chee was prosecuted under Section 377A after a lascar saw him molesting a sleeping Chinese boy at a five-foot passageway off Rochore Road[20].

In April 1941, Captain Douglas Marr, the Deputy Assistant Provost Marshal of the Singapore Fortress Command, was accused of having committed "an act of gross indecency" with a male Malay youth, Sudin bin Daud, who denied being a "catamite". Sudin claimed that on March 13 or 14, he was walking along Stamford Road, a supposed "area for male prostitutes", at night when a car driven by Marr stopped, picked him up and brought him to his boarding house in Tanglin Hill. The offence against Section 377A allegedly took place there, he claimed, whereupon Marr gave Sudin some money and let Sudin take a watch before Sudin left, leaving his shirt there. In his defence, Marr claimed that he had wanted to get "at the root of the homosexual type of vice and I thought, as it transpires very foolishly, that it would be a good idea to question a catamite and to try and find out to what extent soldiers in different regiments were involved". Marr did not deny picking up Sudin, who he claimed approached him, but maintained that he merely questioned him back home to no avail, as he had mistaken Sudin for an Indian and spoken to him in Hindustani. On 16 April and 29 July, after a withdrawn appeal by the prosecution, Marr was acquitted of the charge, despite the fact that Sudin's shirt was found in his room[21],[22],[23],[24],[25]. Sudin, who had pleaded guilty to the act of gross indecency and theft of the watch, was sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment on 27 March[26].

In May 1941, Gunner Ernest Allen of the Royal Artillery became the only European convicted under Section 377A after witness Chan Yau testified that in March, he and Allen had committed the alleged offense in an Anguilla Road house. Allen denied the allegations, claiming that he had hired Chan to get him a girl. Allen was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment[27],[28].

In July 1941, a case involving Mr. Griffith-Jones who admitted "he had been addicted to homosexual practices" and two Chinese locals, Tan Ah Lek and Lim John Chye, who extorted and attempted to extort money from him by threatening to expose him, went to court. The European, who "held a responsible position in a Singapore firm", first came into contact with Lim in January 1939, when Lim wrote a letter to him asking for $5 to keep silent. By 1940, Griffith-Jones had paid him over $1,000, while the English-speaking Tan had extorted and tried to extort a total of thousands of dollars from Griffith-Jones from the end of 1938, even extracting monthly payments from him. On 30 July, he was sentenced to five years imprisonment[29],[30],[31].

Labouchere Amendment

The term "gross indecency" used in Section 377A was based on the wording of the Labouchere Amendment, also known as Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 of the UK. It was not a euphemism for buggery or sodomy, which was already a crime but rather, any other sexual activity between men.

Wording

It was worded thus:

"Any male person who, in public or private, commits, or is a party to the commission of, or procures, or attempts to procure the commission by any male person of, any act of gross indecency shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted shall be liable at the discretion of the Court to be imprisoned for any term not exceeding two years, with or without hard labour."

The almost identical phrasing between the Labouchere Amendment and Section 377A is the best evidence that the latter was derived from the former.

Reason for enactment

Henry Labouchère.

In the 1880s, Britain was in the grip of a moral panic about the extent of prostitution. At the time, it was legal to have sex with teenage girls as young as 13 years of age, while a thriving trade buying and selling girls for prostitution alarmed many middle-class citizens. The Criminal Law Amendment Bill was thus drafted in 1881 to combat this. However, it languished for four years until a new scandal in July 1885 - a newspaper undertaking investigative journalism managed to buy a girl - roused parliament into renewed action.

On 6 August 1885, a member of parliament, Henry Labouchère, proposed a last-minute amendment to the bill making “gross indecency” between males an offence. There was hardly any debate although one member of parliament, Charles Warton, questioned whether Labouchère's amendment had anything to do with the original intent of the bill, namely, the prohibition of sexual assault against young women, and prostitution. Speaker Arthur Peel responded that under procedural rules any amendment was permitted as long as Parliament permitted it.

Without a record of a debate, it is difficult to know what the UK Parliament’s intention was with respect to the “gross indecency” clause. But if one considers that the Amendment Bill as a whole was designed to address prostitution and human trafficking, and if one realises that not only was female prostitution rife, but so was male prostitution, one can more or less guess why. The main part of the Criminal Law Amendment Act was gender-specific about girls as victims. Without the Labouchere Amendment, it would not have addressed male prostitution at all.

Punishment

The former Attorney-General, Sir Henry James, while supporting the amendment, objected to the leniency of the sentence, and wanted to increase the penalty to two years' hard labour. Labouchère agreed, and the proposed amendment was tacked onto the full Criminal Law Amendment Bill. The latter was rushed through and passed as the Criminal Law Amendment Act in the early hours of 7 August 1885.

Vagueness

As a result of the vagueness of the term "gross indecency," this law allowed juries, judges and lawyers to prosecute virtually any male homosexual behaviour where actual sodomy could not be proven. The sentence was relatively light compared to sodomy, which remained a separate crime.

Prosecutions

Oscar Wilde and his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas.

Alan Turing, Great Britain's mathematical genius who was sentenced to chemical castration under the Labouchere Amendment.

Lawyers dubbed the Labouchere Amendment or Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, the "Blackmailer's Charter". It was ceremoniously invoked for the first time to convict the celebrated author Oscar Wilde ten years later, in 1895. Wilde was given the most severe sentence possible under the act, which the judge described as "totally inadequate for a case such as this."

The brilliant mathematician, logician and cryptanalyst Alan Turing was convicted under the same law in 1952. In September 2009, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued a postmortem formal apology to Turing for his “appalling” and “utterly unfair” treatment just because of his homosexuality. Turing's work led to the breaking of World War II Germany’s Enigma codes as well as developing theories which would ultimately result in the development of the modern computer. Despite his genius and contributions, he was charged for a felony and lost his security clearance and his job. He was sentenced to chemical castration with female hormones in lieu of a prison sentence. Two years later, he committed suicide by poisoning himself with cyanide[32].

Repeal

The law was repealed in part by the Sexual Offences Act 1967 when homosexual acts were decriminalised in England and Wales, with remaining provisions being deleted later.

Singapore's Section 377A

Singapore's Section 377A is descended from the Labouchere Amendment[33]. There is no compelling evidence to support the legend that lesbians were not included in similar legislation all across the Commonwealth because Queen Victoria refused to believe that they were capable of such behaviour.

In the local context, "gross indecency" is a broad term which, from a review of past cases locally, has been applied to mutual masturbation, genital contact, or even lewd behaviour without direct physical contact. As with the former Section 377, performing such acts in private does not constitute a defence. There has never existed any law in Singapore equally specific to non-penetrative lesbian sex. Although Section 377A has been in the statute books since the 1930s and was retained even after the Penal Code review of October 2007, it is only sporadically enforced. At the conclusion of the debate on the Parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A in 2007, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong promised that his government would not "proactively enforce" the statute.

However, its presence is used to justify much of the discrimination faced by gay men in Singapore. Some examples are the prohibition by the Ministries of Education and Defence of teachers and higher-ranking military personnel from coming out, and curtailment of employment opportunities and promotion in these sectors. It also influences censorship guidelines by the Media Development Authority which prevents positive portrayals of LGBT people in films and the broadcast media and public advertisements targeting the LGBT community (see main article: Singapore gay censorship).

After the erstwhile Section 377 was replaced by the current law criminalising sex with corpses, it has become a standing joke in the LGBT community that in the Penal Code, gay sex (377A) is now sandwiched between sex with dead bodies (the new Section 377) and sex with animals (Section 377B, "Sexual penetration with a living animal").[34]

Lee Kuan Yew's statement about not prosecuting consensual gay sex, 2000

Interview-based US radio show producer Terry Gross.

On 24 October 2000, Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew was interviewed by female news anchor Terry Gross of the US' National Public Radio:

Gross: ...I want to just get back to something we were talking about earlier, which is certain things that are illegal in Singapore. What are the laws against homosexuality in Singapore?

LKY: Well, we are with British 19th centuries law on homosexuality which is on the statute book. But we have not prosecuted anybody for homosexuality for the last 40, 50 years. What is on the statute book, and if you molest somebody and try and make him a homosexual, particularly if he's a minor, then the law will be enforced. It's a question of judgement. Once we conclude that homosexuality is also a DNA problem, then you've got to approach the punishment in a different way. And if you have consenting adults, well, God bless both of them. But let's...

Gross: God bless both of them only if you find DNA evidence, or...

LKY: No, no. Only if they do not inveigle and draw in innocent, young boys who are not with that inclination.

Contradictory events on the ground

In refutation of Lee's pronouncements about not prosecuting consenting adults for homosexual sex, on 23 July 2001, two undercover policemen infiltrated gay sauna Club One-Seven and arrested two men for having consensual oral sex in a locked cubicle (see main article: Police raids at Club One-Seven). They were originally charged under Section 377A which carried a maximum punishment of 2 years in prison.

Only after their defence counsels fought against this, perhaps by pointing out Lee's statements, was the charge amended to one under Section 20 of the Miscellaneous Offences (Public Order and Nuisance) Act for which the maximum punishment was much less severe - a fine not exceeding $1,000 or a jail term not exceeding one month for an initial offence. The 2 men were eventually fined $600 each. This was probably a landmark ruling which set an important legal precedent.

This case eminently demonstrated that verbal assurances from the Government were no guarantee that the police and the courts would not continue to use Section 377A and that it was perfectly legal for them to do so since the law still remained on the statute books. It was only when the accused's lawyers reminded the judges of politicians' oral statements that the charge was amended to a lesser one. Should the defence lawyers themselves have been unaware that such a promise was made and if no publicity was given to the case, the defendants may very well have been charged under the archaic law.

Annis Abdullah case

- Main article: Annis Abdullah case

Minister of State for Home Affairs in 2004, Ho Peng Kee.

The movement to repeal Singapore's original Section 377 was galvanised by the Annis Abdullah case. In November 2003, police constable Annis Abdullah was found guilty of oral sex with a 16-year-old girl and sentenced to 2 years' jail. Although it was consensual, he was charged under the former Section 377[35]. Many letters were written to the press, shocked that in this day and age, consensual oral sex was still a criminal offence.

In response to the public outcry, the Ministry of Home Affairs said that they were reviewing this aspect of the law. In January 2004, the Minister of State for Home Affairs, Ho Peng Kee reiterated in Parliament that the decriminalisation of oral sex was under review, but only for heterosexuals.

Penal Code review

In 2006, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced that it would be carrying out an extensive review of the entire Singapore Penal Code, the first in 22 years. The exercise took over a year and gathered extensive feedback from the public via the press, the Internet and live forums.

Repeal or retain Section 377A?

The most heated debate concerning the major review of the Singapore Penal Code was not over which laws were to be repealed or amended, but over the statute which would be retained, i.e., Section 377A, the anti-gay law.

185 convictions under 377A from 1997 to 2006

In May 2007, Nominated MP Siew Kum Hong queried the Minister for Home Affairs in Parliament about the number of men prosecuted and convicted under Section 377A over the past decade:

Siew Kum Hong: To ask the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Home Affairs, in each of the last ten years, (a) how many prosecutions and convictions have there been under section 377A of the Penal Code; (b) how many of these prosecutions were police prosecutions; and (c) how many of these police prosecutions were the result of proactive police enforcement.

Wong Kan Seng: The statistics on the number of persons convicted under section 377A (Outrages on decency) of the Penal Code, between 1997 and 2006 is shown below. Prosecution statistics are not available. Police does not proactively enforce the provision.

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 16 | 31 | 30 | 23 | 25 | 11 | 13 | 4 | 7 |

Arguments raised

Map of the world showing the status of LGBT rights in each country.

Advocates of the repeal often cited reasons of civil liberty, human rights, and increasing scientific evidence that homosexuality was inborn[36] and found in nature[37].

Britain, the former British colony of Hong Kong, and Australia have since repealed laws prohibiting sex between men in 1967, 1991 and 1997 (in the state of Tasmania, the last Australian state to do so) respectively. India effectively repealed her Section 377, by having it "read down" initially in 2009 (see video) and finally in 2018. Fiji was the first Pacific island nation to repeal her version of Section 377 in 2010[38],[39]. Elsewhere in East and Southeast Asia, apart from Singapore, only Myanmar, Malaysia and Brunei, all former British colonies, and recently Indonesia's Aceh province (applicable only to Muslims), continue to criminalise sex between men.[40]

Opponents of the repeal based their arguments on the conviction that to decriminalise homosexuality would result in a breakdown of the family unit, compromise Singapore's position on procreation, and lead to future undesirable scenarios such as the approval of bestiality and paedophilia.

They also emphasised the wishes of the putative conservative majority to retain 377A. This was despite there being no formal survey or census done specifically on the topic. In various Singaporean online forums, such as Reach, and the AsiaOne Forum, strong opinions such as homosexuality being a genetic disease, the existence of a militant gay agenda originating from the West, homosexuality being a product of Western decadence incompatible with Singapore, were repeatedly posted. Conversion treatments, such as those by NARTH, were also recommended.

Forums organised

In the lead-up to the overhaul of the Penal Code, forums were organised to discuss the issue of homosexuality in Singapore and the repeal of Section 377A.

A seminar entitled, "Christian Perspectives on Homosexuality and Pastoral Care" was organised by Safehaven, a ministry of the Free Community Church. It was held at the Amara Hotel on 10 May 2007.

PAP MP Baey Yam Keng and NMP Siew Kum Hong look at gay activist Alex Au as he makes a point during the Section 377A repeal forum organised by W!ld Rice.

During the dialogue, Dr Tan Kim Huat, who was the Chen Su Lan Professor of New Testament and Dean of Studies at Trinity Theological College said, "Singapore is a pluralistic society...There must be spaces for it", referring to homosexuals in society. This was the reason he gave for supporting the repeal of Section 377A (see video:[41];[42]).

Another forum to discuss the repeal of Section 377A was organised on Sunday, 15 Jul 07 by theatre company W!ld Rice in conjunction with Happy Endings: Asian Boys Vol 3, a gay play that was then being staged. The forum, held at the National Library, attracted some 250 people.

For the first time in the history of forums on gay issues in Singapore, a member of parliament from the ruling People's Action Party, Baey Yam Keng, and a Nominated Member of Parliament, Siew Kum Hong, were part of the 5-member panel convened to debate the issue.

Baey publicly voiced his support for the law to be repealed, saying, "Personally, I think that the whip should be lifted for a very open debate and open expression of opinion by the MPs. And if that is so, I would vote for a repeal of the act."[43]

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) was quoted in The Straits Times of 18 September 2007 saying that public feedback on the issue had been "emotional, divided and strongly expressed", with a majority of people calling for Section 377A to be retained.[44] The MHA also said that it recognised that "we are generally a conservative society and that we should let the situation evolve".

Video appeals and online campaigns

The prospect for the repeal of both Sections 377 and 377A in Singapore captured the attention of gay activists worldwide. In August 2007, on a visit to Singapore, award-winning movie star and thespian Sir Ian McKellen made an appeal to the authorities to get rid of this remnant of British colonial law, just as his country of origin had done[45]:

On 3 October 2007, another online appeal was launched via the website Repeal377A.com to gather signatories for an open letter to the Prime Minister calling for the repeal of Section 377A. In response, a counter-petition on the website Keep377A.com was set up by entrepreneur Martin Tan to give citizens a channel to voice support for the Government's retention of the law. By 1:30 p.m. on 20 October, Keep377A had overtaken Repeal377A by 7,068 to 7,058 signatories in just two days of its launch.[46] (The content of the Keep377A.com website was removed in 2009, although its web address remains. This may be evidence that the resolve of the Keep377A camp was weaker than that of the proponents of repeal, despite claims of the former to have garnered more support in the form of signatures.)

On 12 October 2007, in an initiative headed by impresario Alan Seah, leading members of Singapore's arts fraternity, both gay and straight, took part on a promotional rap video titled Repeal 377A Singapore!. It was produced and directed by Edgar Tang and theatre celebrity Pam Oei[47]:

Concerned with what was perceived as the video's narrow presentation of issues, a "Families Petition"[48] was launched by an independent focus group FamilyOverFreedom to run until 9 August 2015 as an awareness campaign aimed at educating the middle ground of undecided voters on the potential long-term impact of a repeal on the institution of the family.

Open letter to the Prime Minister

- Main article: Open Letter to the Prime Minister to repeal Section 377A

Presenters of the Open Letter to the Prime Minister - Ivan Heng, Alan Seah and Pam Oei.

On Friday, 5 October 2007, an Open Letter urging the abolition of Section 377A was organised online [49].

The 400-page letter which was supported by 8120 signatories was hand-delivered to the Prime Minister's Office at The Istana on Monday, 8 October 2007 at 2:30pm by co-organiser Alan Seah, theatre director and actor Ivan Heng and actress Pam Oei.

Credibility of Keep377A.com and Repeal377A.com

As online petitions, both websites suffered the same doubts regarding the credibility of the numbers of their signatories. There was no mention of whether technical measures were taken to ensure that multiple-voting by the same person was prevented.

In addition, the opening page of Keep377A.com was amended to include the following conclusion:

"Take time to hear from friends who are gay so that we too can understand their point of views personally. In our democracy, we can learn to agree to disagree, peacefully and respectfully."

The statement was incongruous with forum postings in other parts of the site which repeatedly used derogatory terms and called for Section 377A to be actively enforced.

Research cited by Keep377A.com

One of the references cited within Keep377A.com was a 2005 research article titled "Singaporeans’ Attitudes toward Lesbians and Gay Men and their Tolerance of Media Portrayals of Homosexuality",[50] written by Benjamin H. Detenber and Mark Cenite of the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University. The article reported findings on the attitudes of Singaporeans towards homosexuals, with an emphasis on the comfort of viewing homosexual acts in the mass media. The conclusion highlighted a significant level of negativity. It was not, however, mentioned in the article whether this negativity translated into a specific desire to criminalise homosexual acts. The objectives of the research also did not involve gauging attitudes relating to legislation. A follow-up study by Detenber in 2010 revealed a softening of attitudes towards homosexuality:[51].

Copycat sites

Towards the end of October 2007, at least one copycat site emerged - Support377A.com. Created in virtually the same format as its predecessors, it nevertheless only featured letters to forums against the repeal, and supposed church sermons given on the subject by the Cornerstone Community Church and the Church Of Our Saviour.

Parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A

- Main article: Parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A

Organisers of the parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A - George Hwang, Tan Joo Hymn and Dr Stuart Koe.

In the second weekend of October 2007, a parliamentary petition to repeal Section 377A was organised by human rights lawyer George Hwang, CEO of LGBT web portal Fridae.com Dr Stuart Koe and housewife Tan Joo Hymn [52]. It was revealed during a press conference that it had garnered 2,519 signatures from Singaporeans and Singapore residents (see video:[53]).

The parliamentary petition was a democratic instrument that had lain dormant until resurrected by its organisers. The last time such a petition was presented to Parliament was over 20 years ago. The current one was endorsed by the Clerk of Parliament and scheduled to be presented by NMP Siew Kum Hong on Monday, 22 Oct 07.

Parliamentary debate

On Monday, 22 October 2007, Nominated Member of Parliament Siew Kum Hong tabled a petition to the Parliament of the Republic of Singapore in support of the repeal of Section 377A (see videos:[54],[55],[56],[57],[58]). A petition is required to pass through the scrutiny of the Public Petitions Committee in order for the issue to be fully debated in Parliament. The debate which ensued regarding the petition was the most heated in recent Parliamentary history.

The most impassioned opposition to the petition was provided by fellow NMP Thio Li-ann, imploring the government to retain Section 377A (see videos:[59],[60],[61],[62]).

There were Members of Parliament, however, who spoke up in support of repealing Section 377A or to highlight its legal and moral inconsistencies. They were PAP MPs Charles Chong (see video:[63],[64]), Baey Yam Keng (see videos:[65],[66],[67] ) and Hri Kumar Nair (see videos:[68], [69],transcript of speech). (For a complete list of MPs who spoke regarding Section 377A, see: [70])

PAP MPs who spoke up in favour of repealing Section 377A - Baey Yam Keng, Charles Chong and Hri Kumar Nair.

Other PAP backbenchers, while endorsing the retention of Section 377A, did offer words of support for the gay community (see video).

Ms. Indranee Rajah, a PAP Member of Parliament and former chairperson of the Government Parliamentary Committee for Law and Home Affairs, reiterated the Ministry of Home Affairs' "assurance" that it would not actively prosecute people under that Section. "But in recognition of the fact that there is still quite a strong majority uncomfortable with homosexuality, the Section must stay," she said. However, she suggested that Singaporean society could evolve to accept homosexuality in the future (see video:[71]).

Disappointingly, opposition MP and Workers' Party chairperson Sylvia Lim did not take a stand regarding the repeal of Section 377A (see video:[72]). She proposed the setting up of a Select Committee to scrutinise the wording and execution of the Penal Code and to comprehensively archive and make publicly available feedback from all civic groups.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong makes his concluding speech on the debate over the repeal of Section 377A.

In his concluding speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong highlighted the point that Singapore was "basically a conservative society" with many being "uncomfortable with homosexuals, more so with public display of homosexual behaviour" (see videos:[73],[74],[75],[76],[77] and transcript of speech). However, as recognition that homosexuals “are often responsible, invaluable, and highly respected contributing members of society”, the government would not "proactively enforce Section 377A on them."

Other important statements which the Prime Minister made, revealing Singapore's concept of human rights, were that his government did not "consider homosexuals a minority, in the sense that we consider, say, Malays and Indians as minorities, with minority rights protected under the law" and that it would not "allow or encourage activists to champion gay rights as they do in the West."

He said, "The decision on whether or not to decriminalise gay sex is a very divisive one and until there is a broader consensus on the matter, Singapore will stick to the status quo."

The eventual decision by Parliament was to retain Section 377A. (See archives of all parliamentary speeches made with regard to the Penal Code review on Monday, 22 Oct 07 and Tuesday, 23 Oct 07).

The incongruity of decriminalising oral and anal sex for heterosexuals but not for male homosexuals was highlighted in the international media[78]. It could also be argued that with the repeal of Section 377, penetrative sex between gay men was henceforth legal while non-penetrative sex remained illegal!

Repealing the non-gender specific Section 377 while retaining Section 377A, which criminalises sex specifically between men, effectively served to enshrine discrimination against MSM (men who have sex with men) in Singapore's legal system. Whether this was constitutional or not was thrashed out in the courts several years later.

Reaction of the public

Subhas Anandan, president of the Association of Criminal Lawyers.

While conservative Singaporeans who had agitated for the retention of Section 377A were pleased, the LGBT community and more progressive factions were enraged.

Subhas Anandan, president of the Association of Criminal Lawyers in Singapore, questioned the rationale for not repealing Section 377A in a Channel NewsAsia interview:

"If you are a homosexual or a lesbian, I think you can get into trouble. We are talking about an inclusive society and being more broad-minded. Why do we want to keep these people away, out of the circle? I think we should be more broad-minded, more sympathetic and allow these people to be included in our society."[79]

Consequences of retention

The debate over whether or not to repeal Singapore's anti-gay law attracted the attention of the international media (see video), as it was perceived to be a bellwether of Singapore's human rights record.

In view of the lack of precedent of there being a law in the Penal Code retained only for symbolic reasons, not to be enforced, plus the ambiguity over what constituted "gross indecency", and the repeal of the original Section 377 criminalising carnal intercourse against the order of nature, some academic lawyers have argued that ironically, homosexual anal sex in Singapore was no longer illegal even though the apparently less abhorrent gay oral sex still was [80].

In January 2008, subsidiary legislation was implemented to amend the schedules of various criminal statutes so as to bring them in line with the recent Penal Code reforms which took effect on 1 Feb 08. One of the changes was that after the latter date, all persons convicted under Section 377A would no longer need to be registered, i.e. they would not have any criminal record for this offence [81]. At the time of writing, the legal and social implications of this were still unclear.

K Shanmugam: S'pore "not ready" to repeal 377A

On Thursday, 2 July 2009, a New Delhi high court issued a landmark ruling which overturned Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a 150-year-old British colonial law criminalising penetrative homosexual sex (see video:[82]). 3 days later, on Sunday, 5 July 2009, Law Minister K Shanmugam was asked by female grassroots leader Khartini Abdul Khalid during a dialogue session at Punggol Central Division whether it was time for Singapore, whose laws were "copied" from India by the British, to repeal Section 377A. Shanmugam replied "no" because Singapore society was "not ready" for it[83].

Singapore's human rights report card

- Main article: Universal Periodic Review: Singapore LGBT issues

On 31 October 2010, at least 8 civil society groups, including the LGBT one, People Like Us (PLU), submitted their views on Singapore's human rights track record to the United Nations ahead of the 1 November 2010 deadline. The move was part of the Universal Periodic Review of all UN member states and was the first time that Singapore's human rights record came under scrutiny by the UN. The discrimination against homosexuals under Section 377A was one of the issues highlighted (see video).

Section 377A actively enforced again

In an apparent reneging of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's word and the government's promise never to apply Section 377A again, the police employed a decoy to entrap an ethnic Indian Malaysian man allegedly cruising for gay sex around the disused cemetary at Jalan Kubor in 2010. This episode of the police entrapment of gay men occurred after almost a decade of cessation of the operations.

Section 377A was again used to charge two men having for having oral sex in a toilet cubicle at Mustafa Centre. The gay community was indignant because the non-gay discriminatory Section 294(a), which criminalises "any obscene act in any public place" irrespective of gender (see below) could have easily been used instead.

Constitutional challenge

- Main article: Section 377A constitutional challenge

Well known human rights and criminal lawyer, M Ravi.

On Friday, 24 September 2010, well known criminal and human rights lawyer M Ravi filed an application in the High Court to challenge the constitutionality of Section 377A on behalf of his client Tan Eng Hong, who was charged for allegedly having oral sex with another consenting adult male, Chin, in a locked cubicle of a public toilet[84],[85]. Ravi's main argument was that Section 377A was fundamentally a provision of the law that fell into the category of laws that expressed human prejudices. A considerable amount of background research regarding the case was done by then NUS law undergraduate Indulekshmi Rajeswari.

Tan was originally charged under Section 377A but to avoid the inconvenience of a constitutional challenge which would set a precedent and open the floodgates to other constitutional challenges, the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) withdrew the 377A charges in mid-October 2010 and substituted charges under Section 294(a) instead.

Section 294(a) of the Penal Code[86] states:

"Whoever, to the annoyance of others does any obscene act in any public place...shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 3 months, or with fine, or with both"

High Court judge, Lai Siu Chiu.

Section 294(a), in contradistinction to Section 377A, does not discriminate against gay men as it applies to anyone who has sex in a public place, regardless of gender. Section 294(a) also carries a lighter penalty of a maximum of 3 months' imprisonment as compared to Section 377A's maximum of 2 years in jail, even for sex in a private environment.

On 10 November 2010, Chin pleaded guilty to the substituted charge of Section 294(a) and was fined S$3,000. In mid-December 2010, Tan also pleaded guilty under Section 294(a) and was likewise fined S$3,000.

During a forum on Section 377A organised by Vincent Wijeysingha and chaired by Mathia Lee on Saturday, 27 Nov 10, M Ravi and Vincent Wijeysingha both spoke regarding the forthcoming constitutional challenge (see video:[87]).

At the hearing of the constitutional challenge on Tuesday, 7 December 10, the Assistant Registrar agreed with the Attorney-General’s application to strike out the case on the grounds that the plaintiff did not have standing ("locus standi" in legal terminology) since he was no longer being charged under Section 377A but under Section 294(a) instead, and therefore the proceedings were frivolous, vexatious and an abuse of process. Tan then appealed to the High Court to reverse the Assistant Registrar’s striking-out decision.

In a judgment dated 15 March 2011, High Court judge Lai Siu Chiu dismissed the first appeal relating to the constitutional challenge against Section 377A filed by Tan Eng Hong[88]. However, she ruled that “a citizen should not have to wait until he is prosecuted before he may assert his constitutional rights” and Tan therefore did undoubtedly have "locus standi"[89], that is, he was sufficiently affected by this law to have a legitimate interest in the issue. Nevertheless, she stated that there was no "real controversy" which required the court’s attention ("real controversy" being legalese meaning that it was not a matter of importance to be decided by a court), thus reaffirming the Assistant Registrar's striking-out decision (see full text of judgment[90],[91]). Many observers regarded Justice Lai's judgment as incongruous, as how could the issue be of no "real controversy" when the law affected the lives of thousands of gay men in Singapore?

M Ravi's appeal against Justice Lai's "no real controversy" ruling took place on Tuesday, 27 September 2011[92],[93],[94],[95]. Owing to widespread publicity by Roy Tan in the LGBT community[96],[97], the court's gallery, for the first time in this particular case, was packed with interested observers. These were the arguments M Ravi used to bolster his case:[98],[99].

Landmark ruling

Court of Appeal judges VK Rajah, Andrew Phang and Judith Prakash.

On Tuesday, 21 August 2012, after nearly a year of deliberation, Singapore’s Court of Appeal, in a 106-page judgment, overturned High Court judge Lai Siu Chiu’s decision on 15 March 2011 when she ruled that there was no "real controversy" which required the court’s attention [100],[101],[102],[103],[104].

The 3 presiding Judges of Appeal, Justices VK Rajah, Andrew Phang and Judith Prakash, found an arguable case on the constitutionality of Section 377A that ought to be heard in the High Court. They explained that Tan was at the outset arrested, investigated, detained and charged exclusively under Section 377A. This, they said, squarely raised the issue as to whether Tan's initial detention and prosecution were in accordance with the law. Secondly, there was a real and credible threat of prosecution under Section 377A.

They said Tan would be allowed to vindicate his rights before the courts based on a finding that there was an arguable violation of his constitutional rights. The judges also wanted to acknowledge that Section 377A in its current form extended to private consensual sexual conduct between adult males, adding that "this provision affects the lives of a not insignificant portion of our community in a very real and intimate way. The constitutionality or otherwise of Section 377A is thus of real public interest. We also note that Section 377A has other effects beyond criminal sanctions." (See full text of judgment in main article: Archive of Court of Appeal judgment in Tan Eng Hong v AG, 21 August 2012).

Another seminal point in the ruling was that the appeal judges were "unable to agree with the AG that violations of constitutional rights only occur when a person is prosecuted under an allegedly unconstitutional law." This corollary of this was that any Singapore citizen had the standing to challenge the constitutionality of a law as long as he felt that his constitutional rights were being violated by the impugned law, even though he had not been charged under it. This groundbreaking implication was first realised and articulated by Roy Tan on the Singapore gay news list (SiGNeL)[105].

Gay couple files similar Constitutional challenge

Long-term gay couple, Gary Lim and Kenneth Chee.

As soon as other stakeholders like Fridae founder, Stuart Koe, realised this, a gay couple in a 15-year relationship, Gary Lim and Kenneth Chee, were encouraged to be the new face of the Constitutional challenge, both to elicit widespread support from the LGBT community and to present a favourable image of the gay community to the general public[106]. Their lawyers were well known human rights campaigner, Choo Zheng Xi, founder of The Online Citizen, Choo's boss, seasoned lawyer, Peter Low, both of Peter Low LLC, and Indulekshmi Rajeswari, who as a law student, had helped M Ravi with the research on the challenge and who after graduation, worked for the law company Myintsoe & Selvaraj. Their case was scheduled to be heard in the High Court on 14 February 2013[107].

Lawyers Peter Low, Choo Zhengxi and Indulekshmi Rajeswari.

M Ravi, on behalf of his client, Tan Eng Hong, filed a separate challenge to the constitutionality of Section 377A. Tan's case was initially slated for slightly earlier, on 25 January 2013[108] but was later postponed to 6 March 2013, later than the gay couple's challenge[109].

Religious and political opposition

On 13 January 2013, Faith Community Baptist Church founding pastor Lawrence Khong told his congregation with Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong in the audience that his church members were committed to “build strong families in Singapore” and by their definition the family unit “comprises a man as Father, a woman as Mother, and Children.”

Khong warned that they "see a looming threat to this basic building block by homosexual activists seeking to repeal Section 377A of the Penal Code."[110]

A statement later released by the church stated, “Reverend Khong used the opportunity to highlight to Mr. Goh that homosexual activists have been increasingly stepping up to challenge this framework, especially in their efforts to repeal Section 377A of the Penal Code – a move detrimental to family and family ties.”[111],[112]

Khong's actions were probably made in response to an earlier meeting in November 2012 by representatives from queer womens' group Sayoni with Minister of Law and Foreign Affairs, K Shanmugam, in which they discussed the multifarious, cascading effects of laws and censorship in Singapore[113],[114],[115],[116],[117]. The minister replied that the "majority’s social acceptance" was needed before there could be any changes in laws and policies[118]. A raging online debate ensued in the mainstream media.

A second pastor, Yang Tuck Yoong of Cornerstone Community Church, later posted a message on his website urging Christians to be “battle-ready” for “not just for this battle, but for the many battles ahead of us” against the “LGBT bloc”. However, he subsequently removed more than 100 words from his original statement after numerous complaints, both from the LGBT community and its mainstream supporters[119]. Researcher Scott Teng, aged 29, subsequently lodged a police report against Yang, saying it was "an incitement of violence"[120].

After a speech at the Singapore Perspectives conference organised by the Institute of Policy Studies on Monday, 28 January 2013, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was asked by a participant, civil society activist Braema Mathi, how the fact that the republic was a secular country reconciled with “an old and archaic law that nearly discriminates against a whole (group) of people”. Lee replied, “Why is that law on the books? Because it’s always been there and I think we just leave it.”[121],[122] The LGBT community expressed their extreme disappointment with his comments.

High Court hearing

Gay couple's challenge

High Court judge, Quentin Loh.

On Thursday, 14 February 2013, the High Court today held the first full hearing of the constitutional challenge filed by gay couple Gary Lim and Kenneth Chee. The case was heard by Justice Quentin Loh and was conducted in chambers, meaning that only the parties who were directly involved in the matter could attend. Chee or Lim were not present for the hearing that lasted three and a half hours. Their lawyers filed a 123-page submission[123].

Arguing that section 377A was constitutional, the Attorney-General said that the law applied to all men, not just self-identified gay men, who have sex with other men; the law “reflects public morality” and "because there is a scientifically-established difference between the public health risks associated with sex between men and sex between women."

Supporting affidavits by Prof Roy Chan, founder and president of Action for AIDS, and Bryan Choong, centre manager and counsellor of Oogachaga, a gay and lesbian affirmative counseling agency in Singapore, to explain the negative effect of Section 377A on homosexual men were not allowed by the judge[124].

Tan Eng Hong's challenge

On Wednesday, 6 March 2013, Justice Quentin Loh heard lawyer M Ravi's arguments on behalf of his client Tan Eng Hong, opposed by Aedit Abdullah from the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC)[125].

Ravi’s case for the repeal rested on 2 articles of Singapore’s Constitution. First, Article 9(1) stated that "No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty save in accordance with law. “Law” here had been conclusively agreed to mean “natural justice”, not just what was in the statute books. Ravi argued that Section 377A did not meet the requirements of natural justice, since it was “inherently absurd, arbitrary [and] vague”. It was absurd and arbitrary because it persecuted people born with an immutable sexual orientation, and vague because its interpretation rested on the extremely subjective concept of “gross indecency”.

Second, Article 12(1) stated "All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law." Section 377A discriminated based on sexual orientation, which had been recognised as contravening legal principles of equality in Hong Kong, India, Nepal, Fiji, the US, Portugal, Chile and Peru. The law was also discriminatory within the homosexual community because there was no convincing reason why gay male sex was criminalised while lesbian sex was legally sanctioned.

The AGC’s case, on the other hand, fundamentally rested on the principle of “public morality”, a concept explicitly referred to in the Constitution. Aedit claimed that the Singaporean public still clearly viewed gay sex as immoral, quoting Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University’s study that found that by 2010, 64.5% of Singaporeans still held negative attitudes towards homosexuals, with 25.3% expressing positive attitudes and 10.2% neutral. He further countered that comparisons of Singapore to Hong Kong, the US and India were invalid, given that their legal systems formally recognised a right to individual privacy, whereas Singapore’s did not.

Justice Loh, who did not appear to be swayed by either side, reserved judgment on the case[126].

Judgment on gay couple's challenge

On Wednesday, 10 April 2013, the High Court released Justice Quentin Loh's 92-page judgment[127].

In it, Loh said that “s 377A essentially addresses a social and public morality concern which our Legislature identified in 1938 and subsequently affirmed in 2007.” Addressing the frequently asked question which was also raised by the plaintiffs, i.e., why retain Section 377A if no one was to be prosecuted under it, Loh stated, “If there’s no prosecution of s 377A offences, that is no ground to say that s 377A is unconstitutional.”

He added, “(D)uring the October 2007 Parliamentary Debates, Parliament considered s 377 and s 377A carefully, and after debating the matter fully, endorsed the repeal of s 377 but chose to retain s 377 A. I can see no basis in this case to interfere given my reasons set out above. It is clear that Parliament saw a reasonable differentia upon which to distinguish between two classes: anal and oral sex in private between a consenting man and a consenting woman (both aged 16 and above) was acceptable, but the same conduct was repugnant and offensive when carried out between two men even if both men were consenting parties. There is therefore no reason to strike down the basis of the classification prescribed by s 377A – viz, male homosexuality – as arbitrary or discriminatory, or on the ground that it does not bear any rational relation to the purpose of the provision.”

He concluded that, “In my judgment, the object of s 377A is clear. It criminalises male homosexual conduct that is not acceptable in our society. Its retention was endorsed by Parliament in 2007… I also find that the purpose of s 377A is not a purpose which is so patently wrong as to render it an illegitimate purpose upon which to base a classification prescribed by the law."

Members of the LGBT community expressed their outrage at the ruling[128].

On 18 April 2013, the gay couple announced that they would file an appeal against the ruling. Stakeholders launched a fundraising campaign on the popular crowdfunding website, Indiegogo[129], to raise S$50,000 to help meet court costs[130]. The campaign video[131] was produced by film directors Boo Junfeng and Loo Zihan. The fundraiser proved to be the most successful in Singapore's history with the amount requested exceeded in a matter of weeks and the final figure totalling over S$100,000. This was testimony to the amount of support that the LGBT community bestowed on the couple, in contrast to the almost non-existent support offered to Tan Eng Hong.

During Pink Dot 2013, Gary Lim and Kenneth Chee were invited to be the flag bearers on the podium but no invitation was extended, nor gratitude expressed to or even mere mention made of the initiators of the constitutional challenge - Tan Eng Hong and M Ravi who clinched the successful court rulings which enabled the challenge to come thus far. This led astute observers like Lisa Li[132],[133], Nicholas Leow[134],[135] and others to comment that the LGBT community indulged in discrimination against its own members - those who were not in relationships and who did not possess the poster-friendly image that the gay couple projected[136],[137]. The discrepancy was redressed to some extent when M Ravi was invited to give a speech the following year at Pink Dot 2014 (see video:[138]).

Change in gay couple's legal team

Senior Counsel Deborah Barker and Queen's Counsel Lord Peter Goldsmith.

On Tuesday, 9 July 2013, Lim and Chee issued a media statement that they had appointed Senior Counsel, Deborah Barker, who was a partner and head of Litigation & Dispute Resolution at KhattarWong LLP, one of Singapore’s leading law firms, to represent them at the Court of Appeal[139].

They had also filed for the admission of Queen's Counsel, Lord Peter Goldsmith, to argue their appeal as co-counsel with Barker. Lord Goldsmith Q.C. was Chair of Asia and European Litigation at Debevoise and Plimpton LLP, and was Attorney-General for England, Wales and Northern Ireland from 2001 to 2007 under Prime Minister Tony Blair[140],[141].

Intervention by Tan Eng Hong